Now that the concussion lawsuit filed by retired National Football League players has apparently been settled (remember: the judge still has to give her approval), it's time to focus on the upcoming football season, and working to make the sport safer at every level of the game.

Sincerest form of flattery

We could sit back and wait for the N.F.L., National Federation of High School Associations (NFHS), USA Football and Pop Warner to lead the way on football safety.

From personal experience over the years, I believe that waiting for national organizations to act and adopting a complete top-down approach would be mistake.

In 2002, after USA Football was formed, I wrote to the organization encouraging it to put safety first by requiring, among other things, that all its coaches have appropriate safety training, and by adopting a concussion policy. I was met by silence.

Seven years later, USA Football finally got back to me, asking me to put together a proposal on ways that MomsTEAM could help the organization make the sport safer. I again recommended that USA Football do more than it was doing on concussion safety, such as by training coaches to teach youth football players Coach Bobby Hosea's "Heads Up" tackling and doing more concussion education of coaches, parents, and players.

Finally, in late 2011, USA Football began adopting some of what we had been recommending for ten years.

I had a similar experience in trying to work with the N.F.L. During my 2008 keynote speech at the National Sports Concussion Symposium, I gave the league a long list it could use to help make the sport safer at the youth level (a list I have been constantly updating; for the most recent checklist, click here). I remember being chided for having the temerity to suggest that the N.F.L. was not doing all it could be doing to improve football safety.

Yet it wasn't too long after that I saw that the league implementing some of my suggestions (such as my recommendation that they join with MomsTeam in sponsoring public service announcements about the dangers of concussions in sports, although the PSAs that ultimately aired were, of course, sponsored solely by the league).

In the fall of 2012, the N.F.L. invited me to its New York City headquarters to present a proposal to the league on ways that I thought MomsTEAM could help them preserve and strengthen the sport of youth football, in part by educating parents, and especially safety-conscious moms, about the dangers of concussions and ways in which the risk of concussion could be reduced.

Like USA Football, the N.F.L. went ahead on its own to implement some of our recommendations (witness N.F.L. Commissioner Roger Goodell's recent visit to Columbus, Ohio, where he co-hosted, with Ohio State football coach Urban Meyer, a safety clinic for 600 mothers of youth football players).

This past June I was invited to a press event at the NFL headquarters, where representatives from a group of national governing bodies for team sports talked about their safety initiatives, which showed just how far behind the NFL and its youth football arm, USA Football, had been until recently. To their credit, they pulled together this meeting to learn from the other national organizations whom I have been advising since 2002 such as US Lacrosse, which has been a leader in making its sport safer.

I say until recently, because I believe that, over the past two years, the NFL, USA Football and Pop Warner have done yeoman's work to catch up on the safety front, to the point where they are now making strides in their safety outreach efforts. The additional $10 million earmarked in the concussion litigation settlement for research is a step in the right direction, albeit a fraction of the money that will be needed to be devoted to concussion research to make the sport safer.

Wanted: Pro-Active Parents

But, as far as the N.F.L., NFHS, USA Football and Pop Warner have come in recent years in their efforts to improve football safety, I still believe, in the final analysis, that football safety is largely up to parents, working in their local communities with all those with a stake in making football safer, including independent football organizations, school boards, school superintendents, athletic directors, coaches, school nurses and psychologists, and other health care providers, and networking with other parents, coaches, administrators and medical professionals at the local, state, regional and national levels to share ideas on what works and what doesn't.

It is up to parents to make sure that football programs adopt best practices based on the latest medical research and technological advances in the identification and treatment of concussions;

It is up to parents to insist that coaches be part of the concussion solution, not continue to be part of the concussion problem. Recent qualitative and quantitative studies have confirmed MomsTEAM's longstanding belief that, more than education about concussion signs and symptoms, it is changing the negative attitude of too many coaches towards reporting and creating a safe concussion-reporting environment that may be the best ways to improve the low rates of self-reporting found in study after study.

It is up to parents to do whatever they can to make sure that their child's coach does not continue to convey the message to athletes that there will be negative consequences to concussion reporting by removing them from a starting position, reducing future playing time, or inferring that reporting concussive symptoms made them "weak", but, instead, creates an environment in which athletes feel safe in honestly self-reporting experiencing concussion symptoms or reporting that a teammate is displaying signs of concussion (and reinforcing that message at home)

It is up to parents to be advocates in their community for creating a culture of safety at all levels of the game, instilling in kids when they first start playing sports positive attitudes about sports safety and concussion that they can carry with them throughout their lives.

It is up to parents, whether it be individually or as members of a booster club, "Friends of Football," or PTA, to raise money to (a) fund the hiring of a certified athletic trainer (who, as we always say, should be the first hire after the head football coach); (b) consider equipping players with impact sensors (whether in or on helmets, in mouth guards, skullcaps, earbuds, or chinstraps); (c) purchase concussion education videos (which a new study shows players want and which they remember better); (d) to bring in speakers, including former athletes, to speak about concussion (another effective way to impress on young athletes the dangers of concussion); and (e) to pay for instructors to teach about proper tackling and neck strengthening;

It is up to parents to make sure that the helmet their child wears fits properly, maintains that fit over the course of a season, and has been properly reconditioned, and, if the football program does not buy impact sensors for the whole team, to consider buying one on their own, weighing the benefits of knowing the magnitude and frequency of the hits that their child is taking to the head against the risk that adding a two-ounce piece of plastic to the inside or outside of their helmet may void the manufacturer's warranty and NOCSAE certification or increase the risk that the protection the helmet's polycarbonate shell provides against skull fractures will be compromised;

It is up to parents to decide for their family whether to allow their child to start, or continue, playing football, not some present or former player, journalist or scientist who takes the position that football is either too dangerous to be played by anyone or safe enough to be played by all (October 25, 2015 update: this is exactly the position adopted by the American Academy of Pediatrics in its 2015 Policy Statement on Tackling in Youth Football in which it leaves parents - presumably in consultation with their child's pediatrician - to "decide whether the potential health risks of sustaining ... injuries [in tackle football] are outweighed by the recreational benefits associated with proper tackling"); and

It is up to parents, when a child sustains a concussion playing the sport, to know what to do to help the child recover, including the need for cognitive and physical rest in the first few days after concussion, when it is safe to return to school and everyday social and home activity, whether their child's school day should be modified to take into account cognitive difficulties experienced after concussion and, in consultation with their child's health care providers, including the athletic trainer, if there is one, to sports.

Call to action

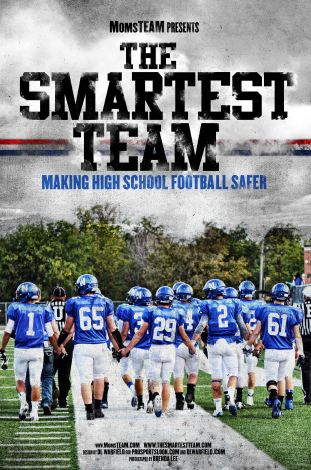

Finally, it is up to football parents like you, if you value MomsTEAM as a trusted source of youth sports parenting, nutrition, hydration, and safety information, to help us spread the word about MomsTEAM, about our PBS  documentary, The Smartest Team: Making High School Football Safer, and about our newSmartTeams initiative

documentary, The Smartest Team: Making High School Football Safer, and about our newSmartTeams initiative

You can help in three ways:

First, you can help make football safer by sending a note to the programming director at your local PBS station encouraging them to find a slot in their fall schedule to air THE SMARTEST TEAM. If they are skeptical about the value of airing yet another concussion documentary, tell them that this one is different: it starts where other concussion documentaries like "Head Games" and "United States of Football" leave off: not just scaring or documenting the concussion problem but showing ways the sport can be made safer right now.

Second, you can help make football safer in your community by suggesting to your school or its PTA that it purchase a DVD of the documentary from our educational distributor, Films For The Humanities (most schools are subscribers already, or it can be purchased a la carte). Why not Invite some former athletes and concussion experts from your community to lead a discussion about concussions after the film.

Third, you can help make football safer by sharing links to MomsTEAM concussion articles with other football parents, coaches, athletic trainers, and PTA presidents, or by distributing copies of key articles, some of which are listed here:

- Concussion Safety Checklist for Parents: 12 ways parents can help protect their kids in contact/collision sport

- Concussions: Parents Are Critical Participants in Recognition, Treatment, Recovery

- Gradual Return to Play After Concussions Recommended

- Coaches: Improve Concussion Safety By Creating Safe Environment For Athlete Self-Reporting

- Honest Self-Reporting Of Concussion Symptoms Critical

I am as convinced as ever that, together, we can preserve and strengthen that uniquely American game: the game of football. It will take work, it will take commitment, it will take dedication, but it CAN and MUST be done.

Brooke de Lench is the producer/director of

THE SMARTEST TEAM: MAKING HIGH SCHOOL FOOTBALL SAFER, Founder and Publisher of MomsTEAM.com, and the author of "Home Team Advantage: The Critical Role of Mothers in Youth Sports (HarperCollins).